Oak Knoll District

of Napa Valley

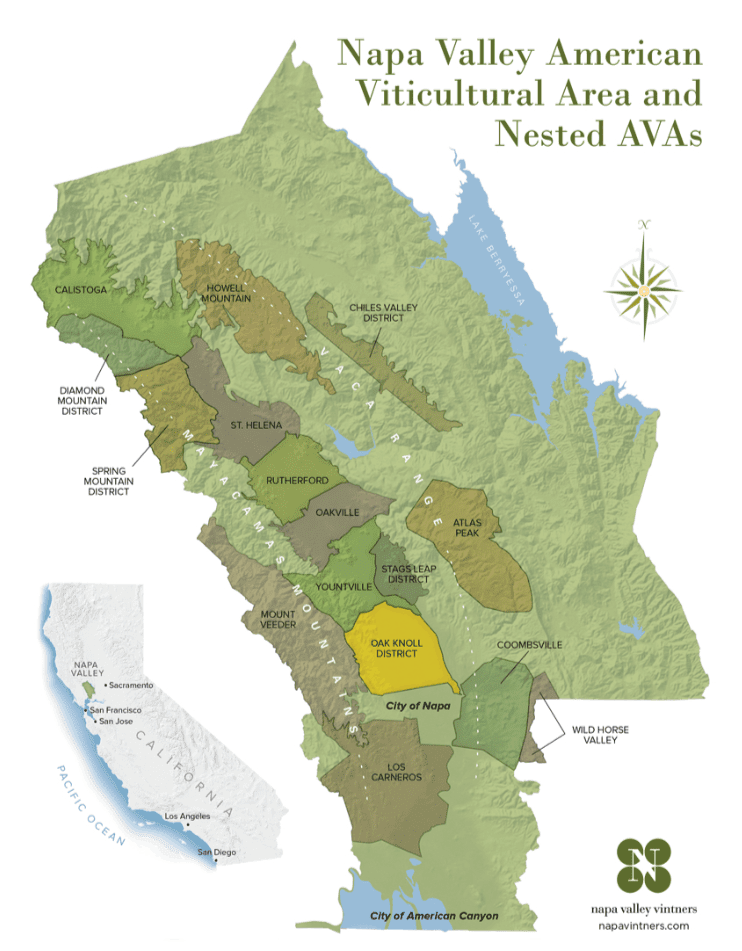

Our estate vineyards are wholly contained within the Oak Knoll District of Napa Valley (OKD for short) which is one of Napa’s sixteen recognized sub-regions. Located near the southern end of the valley, close to San Pablo Bay, vineyards here benefit from a uniquely mild climate and diverse soils.

One of the coolest regions of Napa Valley, we like to say that we have our own “natural air-conditioning”. This cooling is due to two powerful influences, the warm California sun and the cold Pacific Ocean, interacting in the context of our local topography. As temperatures increase during warm sunny days further up-valley, the hot air rises, creating a vacuum. With mountain ranges on both sides of the valley, and Mount Saint Helena blocking the narrow northern end, new air is typically pulled in from the south, from across the bay, and ultimately from over the Pacific Ocean. Currents coming down from Alaska keep the water temperatures off of San Francisco below 60℉ year-round, meaning these ocean breezes are quite cool. These breezes continue into the night, often bringing marine fog in with them. This serves as a protective blanket when the sun comes out again the next morning, preventing us from heating up too quickly. The fog typically burns off by noon, the vines enjoy some sunshine and then the “air conditioning” kicks in again as the cycle continues. This pattern throughout the summer keeps our vineyards as much as 10 degrees cooler than up-valley locations.

The diverse soils of the Oak Knoll District result from a combination of ancient marine sediments and more recent rocky alluvial fans. Millions of years ago, this area was an ocean and the accumulation of sediments over time created a deep base of fertile loam. Over the past thousands of years, the varying flows of local streams and rivers have brought rocks down from the mountains and mixed them in with the richer soil on the valley floor. These are called “alluvial fans” and the largest fan in the Napa Valley was created by Dry Creek, which runs just to the north of our estate. While some grape varieties, such as Chardonnay and Merlot, perform well on the rich loam, others, such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Petit Verdot, excel on the rockier soils found in such alluvial fans.

A long and mild growing season, coupled with soils that range from deep and fertile to rocky and dry, make the Oak Knoll District well suited for an incredible range of winegrapes. Indeed, the OKD is the most grape diverse sub-region in Napa and we grow nine different varieties just within our own estate vineyards.

Over the long growing season, the flavors in the grapes develop fully but slowly. Because of the cooler afternoons and evenings, the grapes maintain their natural acidity which lends a certain brightness to the resulting wines. That levity, that liveliness on the palate, is one of the keys to our estate wines’ storied longevity and food friendliness.

Historical Significance

When Janet Trefethen’s efforts culminated in the recognition of the Oak Knoll District of Napa Valley as an official American Viticultural Area (AVA) in 2004, the approval relied not just on the unique climate and soils described above but also on the area’s long history as a famed grape growing region. That legacy dates back to the 1850s and the origin of winegrowing in California.

Lured by the Gold Rush, Joseph W. Osbourne, a sea captain from Massachusetts, settled in California in 1850. He soon purchased a large tract of land three miles south of Yountville, naming it Oak Knoll. An active member of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, Osbourne had a keen interest in viticulture and in 1852, he and another sea captain, Frederick W. Macondray, brought some of the first vinifera vines to California.

In 1856, Oak Knoll was named the best farm in the state by the California Agricultural Society, and by 1860, its vineyard was the largest in Napa Valley. A champion of vinifera vines to replace the lower-quality Mission variety, Osbourne founded the Napa-Sonoma Horticultural Society with Agoston Haraszthy and then served as president of the statewide organization. His agricultural library was thought to be the largest in the state, and year after year, Oak Knoll grapes and wines won top awards at fairs across Northern California. As wine historian Charles L. Sullivan so sharply put it, “Had he not been murdered by a former employee in 1863, history might well have named him the father of Napa Valley’s fine wine industry.”

As it was, a portion of Oak Knoll became Eshcol, which helped establish Napa Valley’s reputation for quality by winning awards at the 1888 State Viticultural Convention and the 1889 Paris Exhibition. Grape growing on the property survived the twin plagues of phylloxera and Prohibition, but it eventually fell into disrepair before being revived by the Trefethen family in 1968.

Learn